Recent concerns over the banking sector seem to have eased, but have raised uncertainties around the availability of credit and the path of interest rates. Sunil Krishnan assesses the consequences for multi-asset investors.

Read this article to understand:

- Why the mini banking crisis looks to be contained

- Central banks’ balancing act to ensure bank lending is not crushed but inflation is tamed

- The implications for multi-asset portfolios

March and April were overshadowed by the failure of US bank Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and ongoing struggles at Credit Suisse and First Republic, raising concerns over a possible domino effect across the banking sector. Governments quickly stepped in, the US deciding to guarantee SVB’s deposits, while the Swiss authorities asked UBS to purchase Credit Suisse for $3.25 billion and JPMorgan Chase acquired First Republic in a $10.6 billion deal brokered by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC).

Markets remain on the lookout for further weaknesses in the economy

Several central banks also announced a coordinated effort to keep money flowing through the global financial system (and therefore keep credit flowing to households and businesses), using standing dollar swap lines but reducing their frequency from daily to weekly from May 1.1 Markets remain on the lookout for further weaknesses in the economy, but the bank fragility fallout seems to have been contained for now.

Figure 1: Equity markets have recovered (28/02/2023 = 100)

Source: Bloomberg. Data as of May 15, 2023

For multi-asset investors, this raises four key questions: Is there any risk of a Lehman-style financial crisis? What is the medium-term impact on the credit cycle? What does it mean for policy? And what are the investment implications?

Is there a risk of a Lehman-style crisis?

Problems at SVB, First Republic and Credit Suisse partly stemmed from the rise in interest rates, but the precise reasons offer reassurance we are not on the cusp of a systemic banking crisis (also see Ask the Fund Manager).

Briefly, banks have assets, such as securities they hold and loans on which customers pay interest, and liabilities, including deposits people make into the bank. When customers make a deposit, they become creditors of the bank. And they are creditors governments care about because if there's a risk of them losing money, a) they are not all rich and sophisticated individuals, and b) there is the potential for economy-wide confidence to be damaged. Nothing makes people want to queue up outside a bank for their money more than seeing other people queuing up outside a bank for their money.

This is why governments in major economies have introduced deposit insurance: up to £85,000 in the UK, €100,000 in the euro area and $250,000 in the US. The intention is to protect savers’ money, but also help banks rely on this money as a source of funding. If depositors have confidence in the safety of their savings, it is a stickier funding source than, for example, the short-term wholesale funding banks used in the run-up to the global financial crisis (GFC).

The problem with the three banks was that a relatively small portion of their deposit funding was as sticky as it might be for a regular bank. Firstly, they relied mostly on companies and wealthy individuals for deposits. This meant the value of the government guarantee was too low to protect most deposits. Only 12 per cent of SVB’s deposits and 34 per cent of First Republic’s were small enough to be covered by the $250,000 guarantee.2 Therefore, the guarantee wouldn’t stop savers from moving their money out.

Secondly, the banks were not necessarily attractive places to save. We have seen a sharp rise in yields on money markets, while some challenger banks are offering better deposit rates. Established banks haven't kept pace with the yields available on those competing assets. Credit Suisse had suffered deposit outflows for many years – over CHF100 billion in the fourth quarter of 2022 alone – so it could hardly be considered sticky money.3

The government guarantee was too low to protect most deposits

These issues were compounded by the fact bank runs can now happen virtually. Concerns can arise on social media and withdrawals made online in a couple of clicks. Although this could happen to other banks, SVB, First Republic and Credit Suisse were outliers compared to their peers in that they were significantly more reliant on flighty deposit money.

For example, although we also saw social media noise and investor concerns around Deutsche Bank in March, a much smaller proportion of its funding comes from uninsured deposits (c. 70 per cent of its retail deposits are insured). The external noise had died down by the end of April.4

The three banks were also specific cases in terms of assets

Assets were another source of the banks’ difficulties. Banks’ balance sheets tend to have a large pool of liabilities (funds they've borrowed from savers or markets) and a large pool of assets. The equity is the small sliver of difference between these two pools.

SVB had invested most of its assets in fixed-income securities, whose value had fallen steeply as interest rates rose, creating large unrealised losses. When SVB was forced to sell assets to meet redemptions from depositors, those losses became realised and crystallised the bank’s insolvency. In turn, it spooked depositors at First Republic, which was also facing unrealised losses from rising interest rates.5

Credit Suisse suffered serious risk failures in recent years, such as with Greensill and Archegos

The issue with Credit Suisse was one of confidence, which dictated market valuation of the assets. Credit Suisse has suffered serious risk failures in recent years, such as its involvement with Greensill Capital and Archegos Capital Management.6 That impaired confidence in the bank’s assets, reducing the value of that thin sliver of equity – and causing the share price to plummet to $0.88 (from a post-COVID high of $14.49 on February 26, 2021).7

In principle, if there was a big markdown in assets, that kind of concern could arise even in a bank with a stable deposit base. The question would then be whether that bank has enough capital (chiefly equity) to protect the firm’s solvency against the markdown.

But if one thing was a focus of regulators post-GFC, it was ensuring banks have stronger capital bases, particularly in Europe. They are in a much better position today to withstand volatility in their assets or realising losses than in 2007.

For Deutsche Bank, the source of investors’ concern was that it was one of the European banks most exposed to commercial real estate, an asset class that looked challenged in March. But, as a proportion of Deutsche Bank’s overall assets, commercial real estate isn't particularly large, so its capital buffers should be comfortably sufficient for this risk.8

Given SVB, First Republic and Credit Suisse were such outliers in terms of their sources of funding and banks’ capital levels are much more secure than before the GFC, the scope for a near-term Lehman-type domino effect appears limited.

What will be the medium-term impact on the credit cycle?

In terms of medium-term consequences, higher interest rates may increase banks’ funding costs, which could impact their appetite to lend, but the impact of the three banks’ collapse seems limited otherwise. The Fed’s Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey offers a quarterly snapshot on banks’ willingness to lend and the demand they are seeing. The April report indicated relatively little change in supply but evidence that borrowers are, for now, wary of extending themselves into new loans.9

Most banks have benefited from higher interest rates

Looking further ahead, most banks have benefited from higher interest rates, for example by increasing mortgage rates, while not necessarily offering higher deposit rates. This cannot go on indefinitely, but banks may not want to attract a lot of deposits remunerated at a higher rate, in which case they will not be able to expand lending by much either.

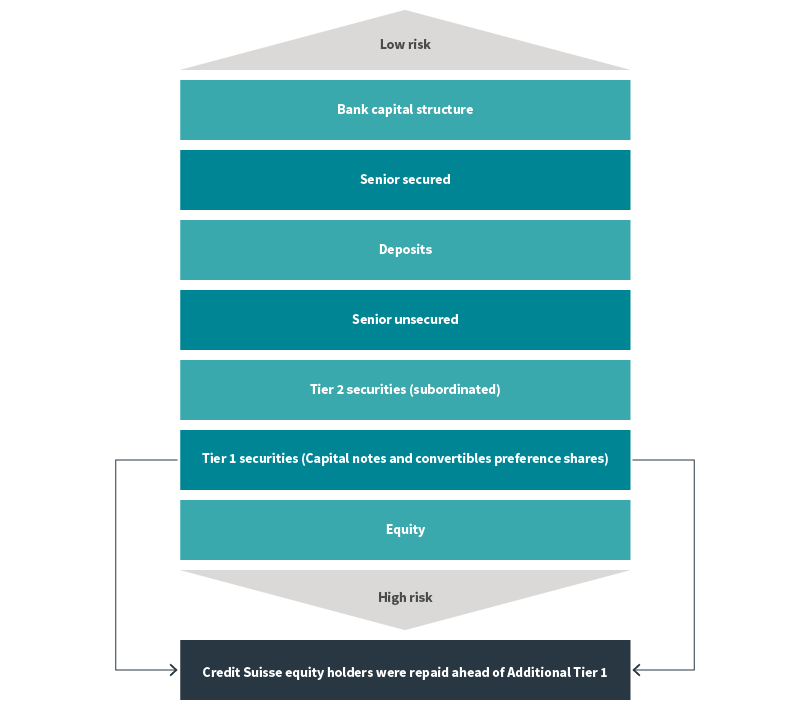

In the markets, the way Credit Suisse was resolved involved big losses for creditors who had invested in “Additional Tier 1” capital securities, which were not expected to lose out ahead of equity (see Figure 2). That has generated uncertainty and volatility for this source of bank capital.10

Figure 2: Order of priority for bank creditors

Source: Aviva Investors, BondAdviser, May 202311

The main concern will remain whether higher funding costs and potentially lower risk appetite affects the supply of credit from banks to the broader economy. It is too early to gauge the precise risks to growth because we don’t know how banks will respond, or whether sectors like commercial real estate will find other sources of funding. But it clearly is an issue to watch.

What does it mean for policy?

Strong jobs and inflation numbers in February pushed up market expectations for the path of interest rates, particularly in the US. But the uncertainty around bank lending means the private sector may now be tightening monetary conditions so central banks don’t have to raise interest rates as much as expected. Evidence from April was mixed, with a strong labour market report but stable inflation in the US.

No one knows how much more policy tightening may be necessary

The difficulty is no one, not even central bankers, know how much more tightening may be necessary. What will credit conditions be in three or four months’ time? How high will inflation be? Both are open questions.

If credit conditions are not severely affected and inflation proves stubborn, interest rates may need to continue rising. However, central bankers must move gradually to have time to assess the knock-on effects of tightening, especially if those are in hidden corners of the financial system.

In the US, interest rate futures are implying a cutting cycle but probably reflect the middle of two outcomes; one where the central bank can keep rates fixed or even raise them slowly; and the other where it is forced into rapid cutting because bank lending declines significantly.

Figure 3: US Fed Funds interest rate futures yield (percentage)

Source: Bloomberg. Data as of May 15, 2023

Investment implications

Last year, the rise in bond-market volatility, decline in bond prices and loss of bond/ equity diversification benefits caused headaches for multi-asset investors. Today, not only does the distribution of bond returns look more favourable, but bonds should be a better diversifier from equities again, whatever the path of interest rates.

If rates continue to rise gradually, bond values may not necessarily decline

If rates continue to rise gradually, bond values may not necessarily decline: yields may have already peaked. In the US, for example, the ten-year US Treasury yield has not yet returned to the high reached four hikes ago.12 On the other hand, if equity markets were impacted by an economic slowdown, central banks would likely begin cutting rates, which would support bond performance.

As a result, we are more constructive than we have been for some time on bonds. We have positions in gilts across portfolios and closed underweights to US Treasuries around the ten-year point.

From an equity perspective, there are still risks, such as a credit-inspired hard landing. However, this risk is heavily debated by investors and was behind a significant amount of the recent pullback. Events might now break more positively than investors expect.

Figure 4: Investors are focused on financial risks (28/02/2023 = 100)

Source: Bloomberg. Data as of May 15, 2023

Moreover, market sentiment is improving slowly, volatility has moderated for bonds and equities, and financial conditions have stabilised. This is creating a more supportive environment for equities. From a sentiment and valuation perspective, there is some margin of safety, particularly in more value-driven sectors.

Figure 5: Market volatility is returning to normal (31/12/2021 = 100)

Source: Bloomberg. Data as of May 15, 2023

In the early stages of the banking panic, cyclical sectors fell almost in unison with banks, creating interesting opportunities. The skew of possible returns now offers more meaningful upside if the economy proves resilient, particularly in sectors like resources. This will be helped by the continued reopening in China and signs of recovery in the Chinese property market.13

Since the scare in March and April, conditions seem to have settled, with markets obsessing over inflation again. Even though the viability of some US regional banks remains debated, it is not causing as much concern. Nevertheless, it was a timely reminder that higher interest rates can expose areas of vulnerability in the economy. Although we are now cautiously constructive on bonds and equities, investors should remain alert.